Central Asia’s Future Melts Away: Water Down the Drain?

Recent Articles

Author: Dr. Eric Rudenshiold

08/28/2025

The accelerating environmental crisis in Central Asia has become impossible to ignore. Across Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, water is disappearing from rivers, reservoirs, and aquifers. Governments have introduced policies to better manage irrigation, modernize canals, and promote regional cooperation, but these steps so far seem likely to only delay the inevitable. The deeper truth is that water itself is vanishing as glaciers retreat at unprecedented speed.

Known for its picturesque snow-capped mountains, glaciers, alpine meadows, and verdant steppe land, this territory once remarked by Marco Polo for its excellent pastures and rich valleys is in danger of turning to desert. Increasingly larger parts of the five Central Asian nations may not be able to sustain human life. Central Asia’s rivers and reservoirs, its crops and cities, many of its power stations and industries, depend on the seasonal runoff of glaciers in the Tien Shan and Pamir mountains.

Breaking the Ice: Hot Times Ahead

Driven by regional temperature increases, the region’s glaciers are melting at a rate four times faster than the global average and far faster than anticipated. The last decade saw the warmest temperatures on record across the region, resulting in nearly 98 percent of Tien Shan glaciers showing signs of retreating. Melt accounts for approximately 80 percent of the total river runoff in Central Asia, feeding the region’s primary water sources: the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. Given the warming climate, at some point it appears the ice and the water will run out.

The Tien Shan’s glacial shelves and snowfall have always served as a critical reservoir that suspends run-off and sustains colder temperatures, storing water for gradual release during the spring and summer. But rapid warming is shifting seasonal precipitation patterns turning snowfall to rain which, in turn, impacts water storage and runoff. The interrelationship between extreme temperature rise, glacial melt, and broader climate change in Central Asia is palpable.

Summer weeks from late July through early August once registered the region’s highest temperatures. However, rapid temperature rise is changing the spring weather cycle to start earlier and the fall season to last longer. The summer melt runoff now peaks several weeks earlier, moving from early August to early July, with profound consequences. The shift means longer, drier late summers, creating conditions that have contributed to the region’s record droughts. Earlier snowmelt also increasingly leaves glaciers exposed to air and solar radiation, making glaciers more susceptible to warming and thereby easier to melt.

It's not Unusual Anymore

Compounding the problem, weather anomalies are becoming the new norm in Central Asia. The warmer conditions have produced heavy seasonal rains, floods, and landslides, resulting in subsequent water and energy shortages. In March 2024, record high temperatures raised snowmelt rates and brought extreme rainfall (instead of snowfall) with consequent floods that devastated significant parts of Kazakhstan. Heavy rainfall similarly produced flooding and a dam collapse in 2021, displacing over 100,000 people in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

But the earlier rainy seasons also produce longer, drier summers. A massive drought in 2021 resulted in over 40 percent of the Central Asian region experiencing water shortages, crop failures, and a devastating livestock die-off. A March heatwave in 2025 struck during the flowering period for Uzbekistan’s fruit crops and Kazakhstan’s spring wheat, likely reducing yields. Increasingly severe and longer droughts now affect two-thirds of Kazakhstan, impacting grain production in two of every five years.

Agriculture, the region’s largest employer, is particularly vulnerable to higher temperatures. Farmers have tried to adapt by shifting planting schedules, but longer and harsher droughts threaten northern Kazakhstan’s rain-fed wheat, which provides food security for the wider region. Intense rainfall and severe droughts reduced Kazakhstan’s wheat harvest in 2024 by 26 percent. Extreme heat not only reduces crop yields, it also undermines labor capacity.

Nearly one-third of Central Asia’s workforce is employed in agriculture, meaning climate change directly impacts livelihoods. The region is predicted to experience extreme heatwaves of up to two months in duration with peak temperatures 4°C higher than today, according to a World Bank report that highlights rising heat mortality and significant economic losses by 2050. Labor migration—already a defining social feature in the region—is expected to accelerate. With hotter summers, drier winters, and volatile spring rains, weather crises are also expected to multiply.

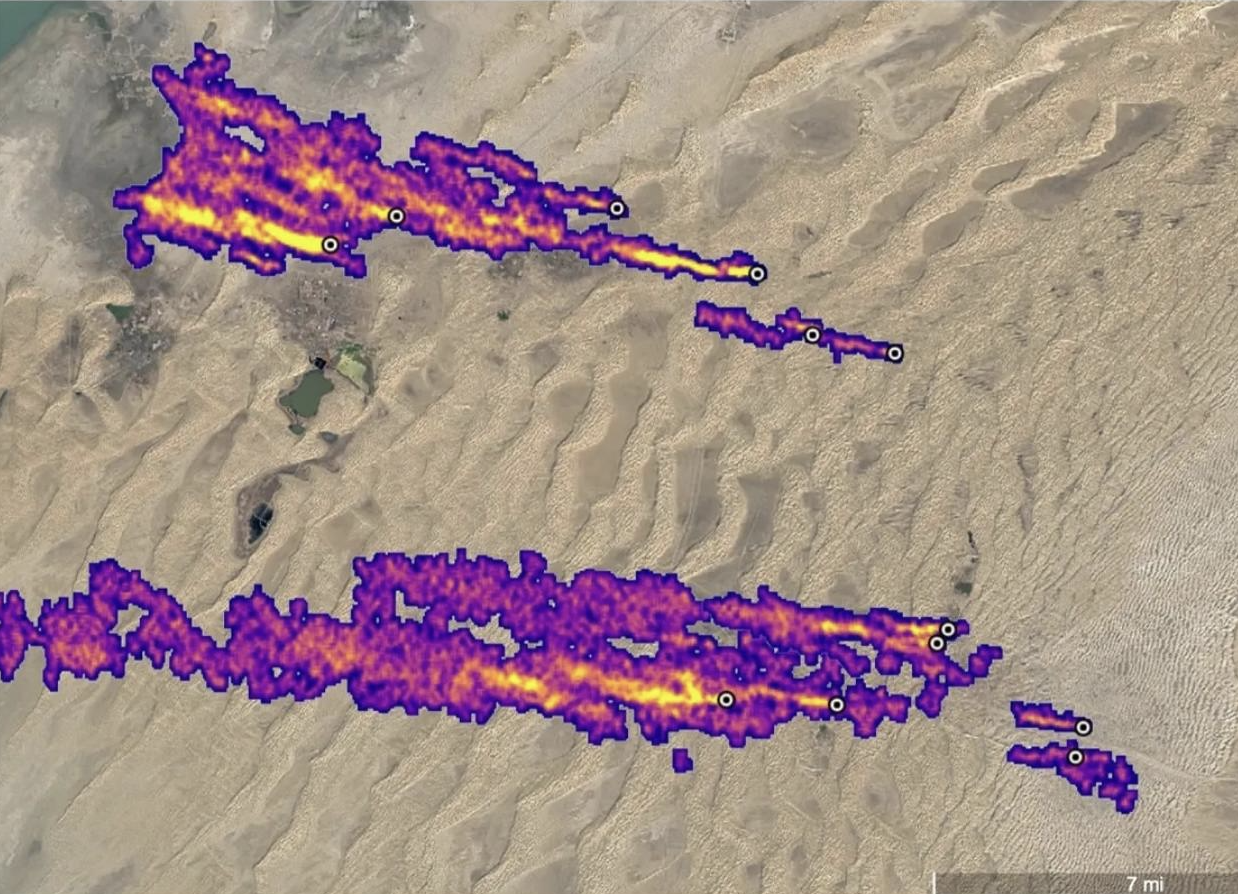

Afghanistan’s massive Qosh Tepa canal threatens to drain up to a quarter of a primary water source for Centra Asia, the Amu Darya river.

Afghanistan’s massive Qosh Tepa canal threatens to drain up to a quarter of a primary water source for Centra Asia, the Amu Darya river.

Policy Responses: Ambition With Some Answers

Governments are not ignoring the crisis. Kazakhstan has invested in canal modernization and irrigation efficiency, including drip irrigation pilots and laser land leveling. Uzbekistan has experimented with water pricing, removing water subsidies for water-intensive cotton, and promoting crop diversification. Water rich Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are adopting tools for managing seasonal water and agricultural irrigation, while utilizing rivers for monetizing hydropower. Turkmenistan is adopting drip irrigation and drought-resistant crops. Collectively, regional organizations are also reviving water-sharing agreements for the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers.

International development institutions have encouraged such efforts—the World Bank and Asian Development Bank funded irrigation reform projects, the European Union encouraged climate resilience initiatives, and the U.S. Agency for International Development sponsored numerous water cooperation dialogues between the five states. The United States has also championed transboundary water cooperation in many of its diplomatic efforts with Central Asia.

But these national and multi-lateral measures all face fundamental limits. Across the five countries, policies speak to carbon neutrality goals and methane reduction, but have concentrated many efforts towards water conservation and preservation. Water infrastructure modernization can only redistribute existing water—it cannot replace glacial runoff that no longer exists. Drip irrigation and lining reservoirs will likely contribute significantly to increased water retention and more efficient use of water but cannot redress the catalytic impacts of temperature rise and glacial decline.

Central Asia’s intraregional cooperation has improved but has historically been undermined by state-to-state competition. Not surprisingly, water insecurity has already been the source of conflicts in Central Asia and could easily trigger future disputes as supplies continue to dissipate. The success of addressing the region’s challenges will only come from successful joint efforts. Temperature rise does not respect borders.

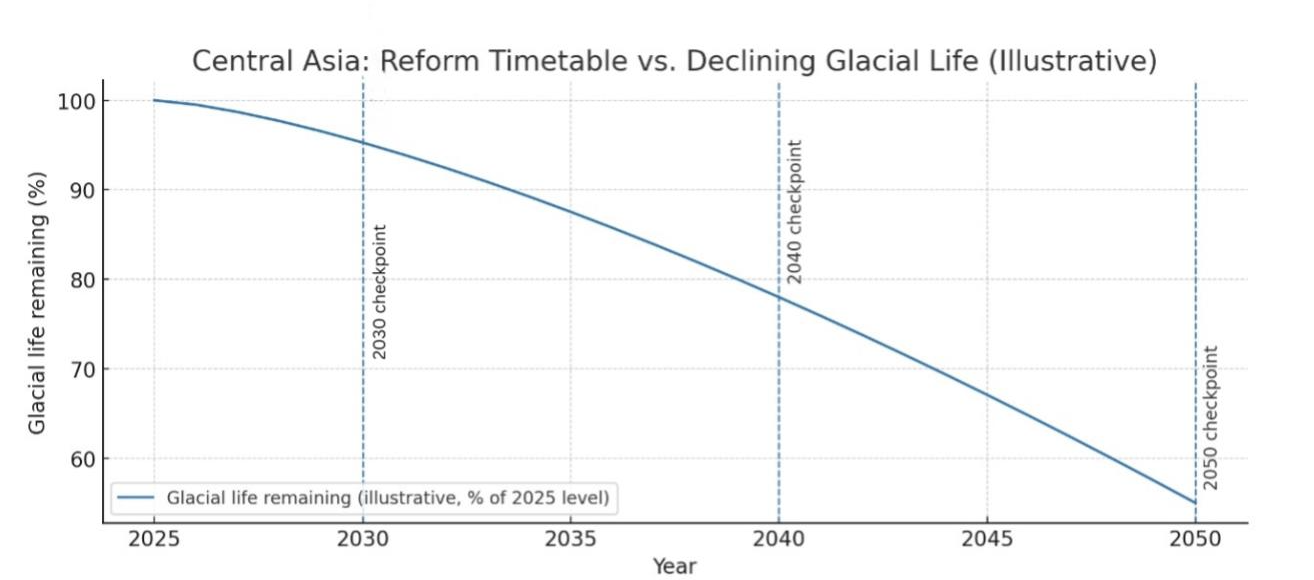

Anticipated glacial decline juxtaposed with UN reform check-in dates.

Anticipated glacial decline juxtaposed with UN reform check-in dates.

Another significant challenge comes from neighboring Afghanistan, Russia, and China. All face similar water security issues and are syphoning off water that Central Asia has depended upon: Afghanistan’s Qosh Tepa canal significantly reduces flow to the Amu Darya River, Russia’s damming and increased use of the Volga River contributes to the serious decline of the Caspian Sea, and China’s greater draw from the Ili and Irtysh rivers reduces flow to Lake Balkhash and regional reservoirs. Transboundary water management agreements are needed and in some cases being discussed. Once again, however, these efforts largely focus on regulating and sharing river runoff, not rising temperatures.

NASA satellite photo capturing massive methane leaks from Turkmenistan.

NASA satellite photo capturing massive methane leaks from Turkmenistan.

Central Asia’s challenge overall is largely environmental, not managerial. Current policy approaches that bolster reservoirs and water usage will not fundamentally change the hydrological reality of diminishing snow and ice. Such policies and management so far seem destined to postpone the inevitable.

Glacial Melt as the True Driver

At the heart of Central Asia’s water crisis is glacial melt driven by rising temperatures. Glaciers are not just one water source among many—they are the foundation of the entire system. Roughly 80 percent of Central Asia’s river flow comes from glacier and snowmelt. Without them, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya arteries of Central Asia will wither, as already evidenced by the 20 percent atrophy in river volume and the 90 percent decline in the rivers’ repository—the Aral Sea.

Temperatures across the region have risen twice as fast as the global average. The Tien Shan glaciers have lost nearly a quarter of their mass in the past half-century. Scientific models predict that in 25 years, Central Asia could lose half of its remaining glacier cover. At that point, river flows will drop dramatically and destabilize irrigation, hydropower, and drinking-water systems.

Unlike over-irrigation or inefficient canals, glacial retreat is not a problem solvable through simple policy reform. Lowering air temperature to slow and even reverse glacial retreat has never been achieved at scale. But, without radical emissions cuts, such as lowering methane levels, the ice will continue to melt, likely at an increasing rate. Absent such fundamental and sweeping change, current efforts seem set to merely prolong the region’s hydro-decline.

That’s a Lot of Hot Air

If rising air temperatures are the primary culprit behind glacial decline, Central Asia’s air pollution is most certainly the trigger. Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan are ranked as the 6th, 19th, 26th, 41st, and 71st most polluted countries in the world based on air particulate exposure. In 2022, satellites detected 184 super-emitter events from Turkmenistan’s gas and oil fields alone. Central Asian cities are correspondingly hotspots for air pollution worldwide, with clear seasonal patterns in Almaty, Bishkek, and Astana, featuring winter peaks from coal-fired heating, and high levels of both winter and summer pollution in Tashkent and Dushanbe.

Central Asia is also responsible for significant methane emissions, with Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan among the world’s leading emitters. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, 28 times more powerful in warming the atmosphere than carbon dioxide and widely prevalent in Central Asia due largely to oil and gas infrastructure leaks, coal mining, and agriculture. The key danger of methane is that it traps and concentrates more heat than other gases, posing a greater threat to the region’s temperature rise.

Eliminating methane will be no easy task. For instance, Agriculture is a methane-source industry which is also the largest employer in the Central Asia region, employing between 25 and 40 percent of the region’s workforce. Reflecting historic investments and traditions, the sector accounts for significant portions of GDP in each country and has seen few concessions so far to the climate.

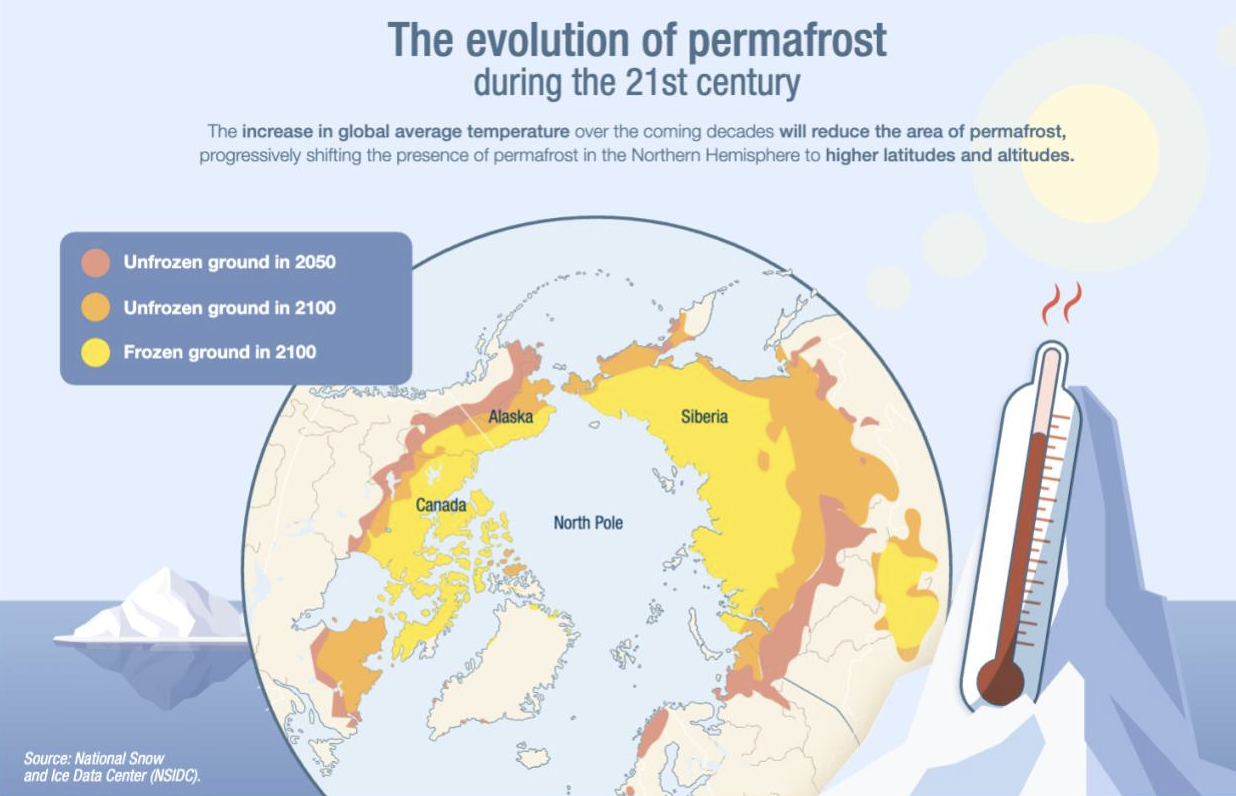

Source: Iberdola - Within 25 years, half of Central Asia’s remaining glaciers are predicted to melt.

Source: Iberdola - Within 25 years, half of Central Asia’s remaining glaciers are predicted to melt.

Perhaps the region’s greatest methane contributor, however, has yet to be fully released. Globally, methane trapped in glacial permafrost is rapidly being released, as glaciers and underlying permafrost dissipate. Formed during the Ice Age, Central Asia’s permafrost contains large amounts of methane and carbon trapped in the decomposed organic matter within. The region’s alpine permafrost deposits are also expected to melt at a faster rate than its arctic equivalent, being closer to the equator. The result for the region could be devastating.

Stopping the Vicious Cycle

As Central Asia’s air temperatures rise ever more rapidly, glacial decay also accelerates, warming and revealing permafrost, which in turn releases trapped methane, that further raises air temperatures, in what appears to be becoming a self-perpetuating downward spiral. The combined effect of methane release from the region’s permafrost, fossil-fuel industry leaks, agriculture byproducts, coal mining releases significantly magnify the region’s warming trend.

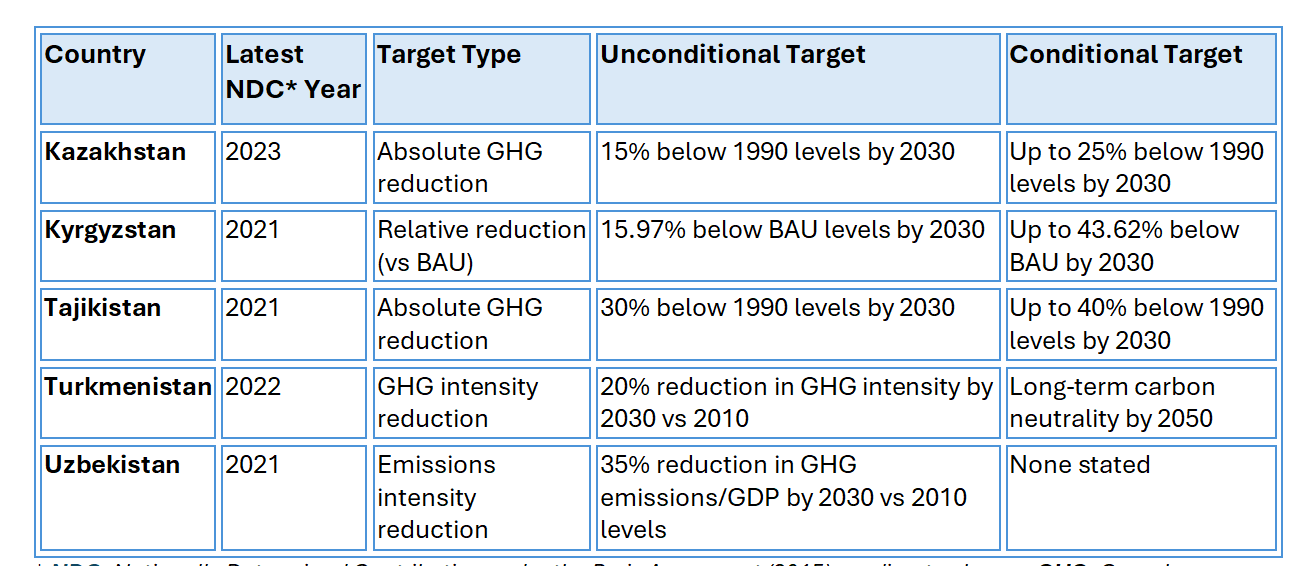

Central Asia’s Climate Pathways: How Far Each State Intends to Go

* NDC: Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement (2015) on climate change. GHG: Greenhouse gas emissions. BAU: Business as usual, if no additional policies or measures, or “baseline path.”

* NDC: Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement (2015) on climate change. GHG: Greenhouse gas emissions. BAU: Business as usual, if no additional policies or measures, or “baseline path.”

Lowering the region’s carbon footprint is key to slowing air temperature rise. While a major player, methane is not the sole culprit in the region. Coal combustion also remains a major contributor to climate warming, as coal dust and particulates hasten snow melt. To varying degrees, all five countries in the region burn coal for generating energy, as they individually are unable to maintain energy security, though change is in the offing.

Unlike a few decades ago when regional power collaboration collapsed, all five Central Asian governments have now embraced a degree of energy cooperation in order to meet their national and regional priorities for energy security and to secure benefits from regional electricity trade. Nevertheless, efforts to promote and adopt renewable and clean energy strategies and to implement smart grids across the region will take time and massive investments. Meanwhile, climate-induced temperature swings place huge demands on the region’s existing, aging infrastructure.

In the interim, most countries in the region default to older technologies, using coal, oil, and natural gas as fuel. For instance, the Kyrgyz and Tajiks burn coal for electricity in winter, since colder temperatures reduce glacial melt and water flow into the hydropower plant reservoirs. Ironically, the region’s warming climate has reduced the number of “winter days” in Kyrgyzstan from 95 in 1991 to 71 days currently, meaning there are now fewer days when burning coal is needed for electricity and there are more warm days for melt to fuel hydro-electric generation.

There is definitely an awareness of a need to act. In 2023, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan joined the Global Methane Pledge, a COP 28 initiative of the European Union and the United States designed to secure voluntary actions to reduce methane emissions from energy, agriculture, and waste. In various high-level statements in support of United Nations Climate Change Conferences, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan all stressed the existential nature of the climate challenges the region shares. However, five different visions were offered for redressing the region’s climate and water woes. Translating lofty COP goals into rapid and coordinated actions to solve temperature rise by all five countries will be difficult, but critical to resolve hydro-carbon industry leaks, agriculture byproducts, and coal mining releases on top of all of the other policy efforts.

The Coming Future: Drought, Migration, and Instability

Absent a shared solution, the implications are profound. Food sources are already under threat. Grain, fruit, and cotton yields will continue to decline. Livestock herding will become untenable in more areas. Desertification will increase, making land less habitable. Higher temperatures will also directly threaten human life, with heatwaves causing illness and mortality.

Environmental migration will intensify. Millions may be forced to leave rural areas for cities, and from Central Asia toward Russia, Türkiye, or Europe. Migration has long been a safety valve for the region’s economies, but huge numbers from climate-driven migration could easily overwhelm existing systems, particularly as Türkiye, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, China, and Russia are all experiencing similar challenges of extended droughts and critical water shortages. Central Asia’s urban infrastructure, remittance-based economies, and political systems will strain under such pressure.

The geopolitical ramifications extend beyond Central Asia, too. Water stress could exacerbate border disputes, as seen in past clashes over irrigation canals between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Reduced hydropower potential could particularly destabilize the entire energy grid. Drought-induced food shortages could force governments to rely more heavily on imports, exposing them to global price volatility.

Avoiding a Dead Heat

Central Asia’s governments are pursuing rational policies: modernizing irrigation, diversifying crops, improving water sharing, adopting carbon-neutral policies, and building hydropower. These efforts are necessary and may buy time. But they cannot resolve the core driver of crisis--the melting of the region’s glaciers caused by rising air temperatures.

The uncomfortable conclusion is that nothing less than reversing regional warming can stabilize Central Asia’s water and climate future. But lowering air temperature has never been achieved through policy. What is needed are radical and innovative efforts across multiple fronts—now. Foremost among these must be efforts at drastically reducing methane and particulate emissions that warm the climate and speed glacial erosion. Anything less appears doomed to fail.

Central Asia has emerged as a vital energy supplier and transport hub in global geopolitics. Yet its most fundamental crisis lies not in pipelines or trade routes, but in disappearing ice. Unless the glaciers remain, the region’s future will slip away with the meltwater.