Beyond the Contract: What Kazakhstan’s Rosatom Deal Says About Its Foreign Policy Balancing Act

Recent Articles

Author: Berik Matebay

06/24/2025

On June 14, Kazakhstan announced the selection of Russia’s state-owned nuclear corporation, Rosatom, to lead an international consortium for the construction of the country’s first nuclear power plant (NPP). This marked a pivotal step in Kazakhstan’s long-term energy strategy. The decision followed a multi-stage evaluation process that assessed each proposal based on technical specifications, safety, construction timelines, localization potential, and financing terms, according to Chairman of the Kazakhstan Atomic Energy Agency Almasadam Satkaliyev.

The government concluded that Rosatom’s proposal was the most advantageous, offering a combination of proven project delivery experience, robust safety features, and favorable financial conditions. On the same day, it was also announced that a second international consortium would be led by China’s CNNC, although further details about this separate project have not yet been disclosed.

Public support for nuclear energy has appeared to be strong. In 2024, a national referendum showed that 71 percent of Kazakh citizens were in favor of constructing a nuclear power plant. The Ministry of Energy shortlisted four companies for evaluation: China’s CNNC offering the HPR1000 reactor, South Korea’s KHNP proposing the APR1400, France’s EDF with the EPR1200, and Russia’s Rosatom with the VVER-1200. After thorough review, the government awarded one contract to Rosatom and indicated that CNNC would lead the development of a second NPP in the future. The selection was guided by a combination of economic, technical, and strategic considerations.

Construction Reliability and Timeline

Construction and operational experience were critical factors in the government’s decision. Rosatom is widely recognized as a global leader in nuclear power plant exports, with six VVER-1200 reactors already operational (four in Russia, two in Belarus) and fourteen more under construction in countries including Turkey, Egypt, Bangladesh, and Russia.

The following map displays the various Rosatom projects within the Caspian region.

CNNC also boasts significant experience, operating seven HPR1000 reactors (five in China, two in Pakistan) and constructing fourteen more. KHNP operates eight APR1400 reactors (four domestically, four in the UAE) with two more under construction. However, a key limitation for South Korea is its inability to independently provide uranium conversion and enrichment services due to a long-standing agreement with the United States which could reduce strategic value for Kazakhstan as it pursues greater fuel autonomy.

EDF’s EPR1200, meanwhile, is a new reactor design that has not yet been built or operated. Its larger predecessor, the EPR1650, has faced major delays and cost overruns, most notably at France’s Flamanville 3 and Finland’s Olkiluoto 3, raising concerns about EDF’s reliability and increasing the perceived construction risk of its proposal.

The average construction timeline varies substantially between technologies. Chinese reactors typically take about six years to complete, South Korean and Russian reactors require around nine years, while French reactors have taken up to 16.8 years. EDF’s Flamanville 3 was delayed by 12 years and saw costs rise from €3.3 billion to €13.2 billion. Finland’s Olkiluoto 3 experienced a 14-year delay, with costs increasing from €3 billion to €11 billion. Delays likely made EDF the riskiest choice from a project execution standpoint.

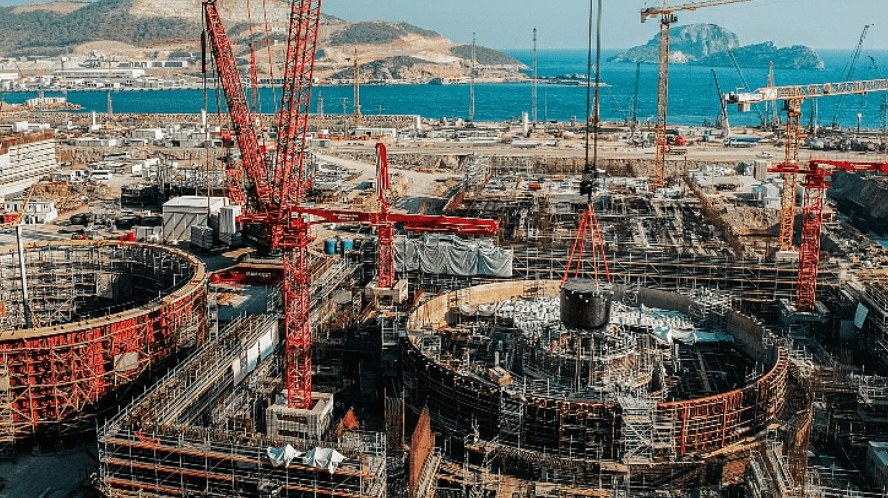

Construction of VVER-1200 Reactors at Akkuyu NPP, Turkey; Photo: Rosatom, 2023

Construction of VVER-1200 Reactors at Akkuyu NPP, Turkey; Photo: Rosatom, 2023

Economic Competitiveness and LCOE

The Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE) is a metric that calculates the average cost of electricity generation over a plant’s lifetime and was central to Kazakhstan’s evaluation. For nuclear power, capital expenditures represent 80-86% of the LCOE. These capital costs are influenced by overnight construction costs and the cost of financing.

According to estimates from the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency and the International Energy Agency based on 2018 data, overnight construction costs were approximately $4,013/kWe for France’s EPR1650, $2,157/kWe for South Korea’s APR1400, $2,271/kWe for Russia’s VVER1200, and $2,500/kWe for China’s HPR1000. Though dated, it is reasonable to assume that the relative cost competitiveness of the Russian, South Korean, and Chinese designs remains similar today.

Several factors contribute to lower costs among these vendors. Reactor standardization across multiple projects enables economies of scale and minimizes design-related errors. Vertically integrated supply chains enhance cost control and project efficiency, while multi-unit construction on shared sites reduces logistical expenses and shortens timelines. In contrast, EDF’s novel reactor design did not benefit from these structural advantages, which contributed to the significant delays observed in its past projects.

Construction of HPR-1000 Reactors at Lufeng NPP, China; Photo: CGN, 2025

Construction of HPR-1000 Reactors at Lufeng NPP, China; Photo: CGN, 2025

Cost of Capital and Vendor Financing

Another key component of LCOE is the cost of capital. An increase in interest rates from 4.2% to 10% can raise the LCOE by a factor of 1.8 to 2.5. For Kazakhstan, securing low-interest financing was critical, especially given its intention to avoid state budget expenditures for the project.

Kazakhstan’s Ministry of National Economy has made it clear that the nuclear power plant must be financed externally. In this context, vendor financing became a decisive factor. Historically, Rosatom has provided loans between $10-25 billion at interest rates of 3-4%, often backed by the Russian government and sometimes including equity participation. Egypt, for example, received a $25 billion loan at 3% interest over a 22-year term. China has also extended significant financing, including $6.7 billion in loans to Pakistan’s KANUPP, typically at interest rates between 1% and 6%.

France and South Korea offered financing but typically under less favorable conditions. EDF’s arrangements often involve partial state guarantees and complex equity structures. South Korea supported the UAE project with a $2.5 billion loan and an 18% equity stake. In contrast, Rosatom’s consistent track record of generous, state-backed financing likely played a critical role in Kazakhstan’s decision, particularly given recent budget constraints driven by increased public spending on social programs and infrastructure.

Technical Specifications

All the proposed reactor designs are Generation III or III+ pressurized water reactors. These designs feature high thermal efficiency (35–37%), capacity factors above 90%, design lifespans of 60 years (potentially extendable to 80), and strong safety systems, including resistance to earthquakes and double containment. Given these broadly similar technical characteristics, the key differentiators in the selection process were cost, construction risk, and long-term fuel supply, rather than performance specifications.

Fuel Supply and Energy Independence

Fuel supply security is a long-term strategic issue. Nuclear reactors require refueling every 18 months, creating an enduring dependence on the chosen vendor’s fuel cycle. France, China, and Russia all operate fully integrated fuel supply chains - from conversion and enrichment to fuel fabrication and spent fuel reprocessing. South Korea lacks domestic enrichment and reprocessing capabilities due to its 1973 agreement with the United States, which restricts these activities. In practice, this means South Korea can only supply fabricated fuel, with upstream processes outsourced to third parties.

For Kazakhstan, this is a significant limitation. As the world’s largest producer of uranium, the country seeks to move up the nuclear value chain. In 2020, Kazatomprom acquired uranium conversion technology from Canada’s Cameco, but enrichment remains a more complex and politically sensitive objective. Kazakhstan currently holds a 10% stake in the International Uranium Enrichment Center in Angarsk, Russia, giving it access to enrichment services, though not full control.

From a trade perspective, China relies heavily on Kazakhstan for its uranium needs. In 2023, approximately 67% of China’s uranium imports came from Kazakhstan, underscoring Beijing’s strategic dependence. France also views Kazakhstan as a critical supplier, particularly after the 2023 coup in Niger disrupted around 20% of France’s uranium imports. President Macron’s 2023 visit to Kazakhstan reaffirmed the importance of bilateral energy ties.

Rosatom, CNNC, and EDF are all considered capable of supporting Kazakhstan’s long-term nuclear fuel ambitions. South Korea’s exclusion from the consortium leadership likely reflects its inability to offer an independent, fully integrated solution.

Conclusion

Kazakhstan’s selection of Rosatom reflects a strategic balancing of economic feasibility, technical reliability, and geopolitical alignment. Rosatom’s strong record in project delivery, cost-effective financing, and vertically integrated fuel services likely made it the most compelling choice for leading the country’s first nuclear project. Simultaneously, the decision to engage CNNC for a second project indicates Kazakhstan’s intent to diversify its technological partnerships and avoid over-reliance on a single supplier. This two-track approach not only enhances Kazakhstan’s long-term energy security but also strengthens its position as an emerging regional leader in peaceful nuclear development.