Not Russia’s Backyard, Not China’s Quarry: Why this Week’s White House Summit with Central Asia is Critical

Recent Articles

Author: Dr. Eric Rudenshiold

11/03/2025

For three decades after the Soviet collapse, the countries of Central Asia and the South Caucasus were internationally regarded as appendages--either of Moscow, which supplied the pipelines and the markets, or of Beijing, which offered cheap loans and an insatiable appetite for raw materials. Their wealth in oil, gas and uranium seemed always to be someone else's opportunity. Their extractive riches, sold at discount prices to Chinese processors and refiners, resulted in less value for domestic budgets. Connectivity was the key problem: bottlenecks of geography, legacy infrastructure, and politics kept the region bound to its giant neighbors.

That is now changing with remarkable speed. The war in Ukraine, Russia's weaponization of energy, and China's slowing economy have together created a once-in-a-generation opening. Across Central Asia and the South Caucasus, leaders are seizing the chance to revamp trade routes, attract investment and, above all, claim control over their economic futures. The Middle Corridor is a trans-Caspian route linking Central Asia to Europe via the South Caucasus and Turkey that has gone from boutique project to become a geopolitical powerline. And the once-unimaginable peace emerging between Armenia and Azerbaijan makes the corridor even more viable than ever.

This shift is not just about roads, rails and ports. It is about agency. The capitals of Astana, Tashkent, and Baku are no longer content to be subordinates to Moscow or middlemen for Beijing. They are working to position themselves as processors and suppliers in their own right, offering oil, gas, uranium and, increasingly, critical minerals on terms that benefit domestic as well as export economies.

Forthcoming Summit Marks a New Chapter

The United States will host the leaders of the five Central Asian republics (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) on November 6 to mark the tenth-anniversary milestone of this U.S.-Central Asia "C5+1" multilateral platform. The White House summit has the potential to be more than symbolic though. Given Washington's strong interest in securing alternate suppliers for strategic minerals and rare earths, the C5+1 Summit could pave the way for far more ambitious economic and value-added cooperation partnerships.

In practical terms, Washington and the Central Asian capitals have identified cooperation in strategic minerals as a key priority heading into this summit. For the U.S., the timing is urgent as the U.S. needs reliable supply-chains for critical minerals away from China's processing dominance. For the Central Asian states, the priority is to capture more of the value-chain at home, rather than being exporters of raw ore to Chinese refiners at a discount. Their aim is to convert extractive potential into domestic processing, refining and higher-value exports—a goal the summit will likely highlight.

The twin significance is that this gathering celebrates a decade of U.S.-Central Asia dialogue, but also sets the stage for deeper cooperation in strategic minerals and value-added industrial development. Rather than just reinforcing the region's infrastructure and trade routes, the summit will give momentum to the next phase: transforming those routes into pipelines of strategic materials and high-technology manufacturing, in which U.S. firms and Central Asian producers will both share stakes.

From hydrocarbons to strategic minerals

The oil and gas business remains the region’s economic bedrock. Western majors such as BP and ExxonMobil have finalized, renewed, and extended commitments in neighboring partner, Azerbaijan; Kazakhstan continues to juggle its massive export volume via routes across Russia and the Caspian; Uzbekistan is still a net importer but pushing exploration of new deposits. Uranium, too, is vital: Kazakhstan is the world's largest producer and will remain indispensable for a global nuclear sector scrambling to cut reliance on Russian supply chains. Astana and Tashkent together account for over 45 percent of international uranium supplies.

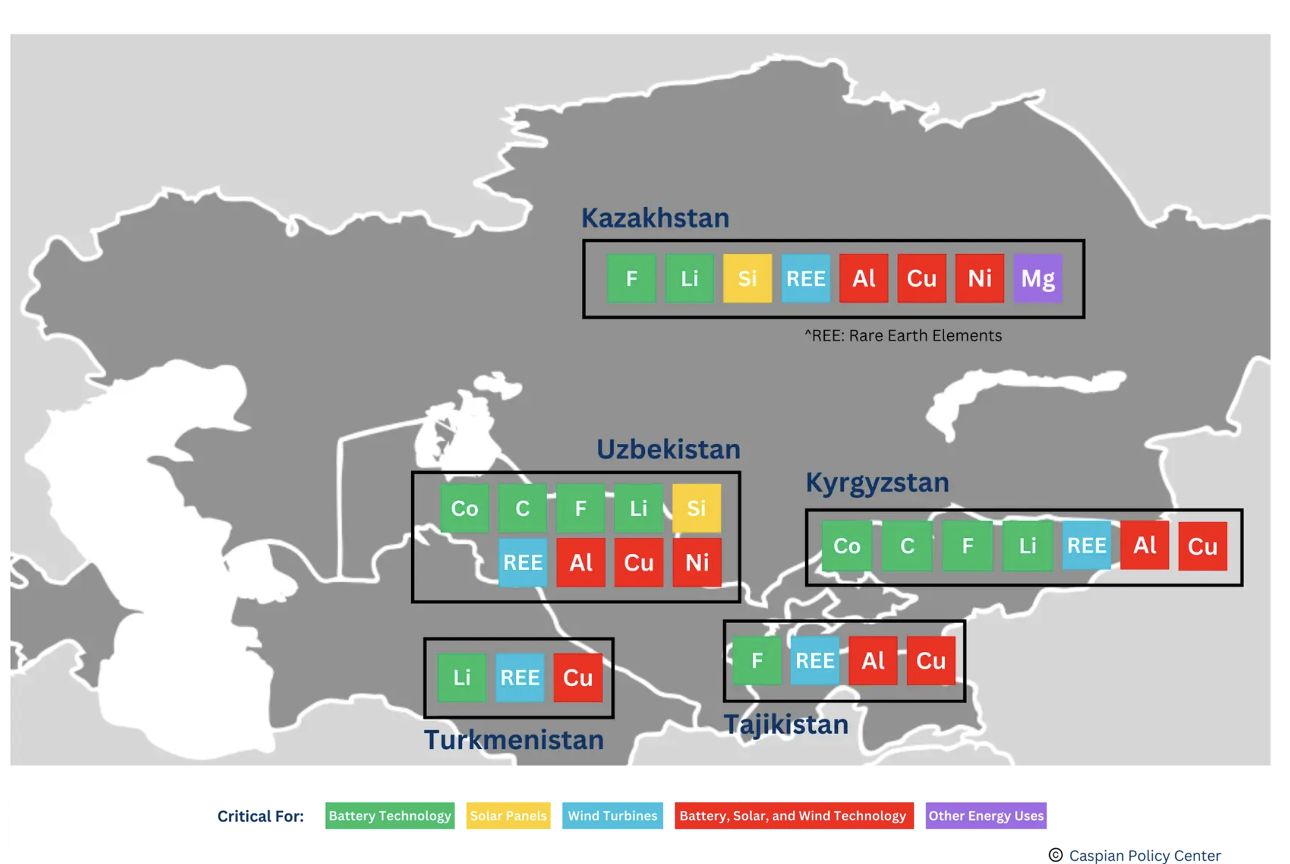

But the next growth engine is clear. Strategic minerals and rare earths--lithium, cobalt, tantalum, rare earth concentrates--are abundant across the region. Most of these are sold cheaply as raw ore and shipped to China, where the refining, processing, and added value take place. Central Asian governments are determined to change that. By inviting Western and Asian partners not just to join in mining ventures, but to finance processing plants and refining facilities in the region. Central Asians aim to capture more value at home while foreign backers get secure, off-take supplies at better prices than from Beijing.

Source: Caspian Policy Center

Source: Caspian Policy Center

This is a decisive pivot. Selling raw ore to China at deep discounts is easy but disempowering. Entering partnerships with international investors to build local processing and refining capabilities creates economic sovereignty and raises revenues. A metric ton of raw lithium ore might be worth a few thousand dollars, but once processed into battery-grade lithium carbonate can be worth many times more. The value-added is immense and that arithmetic is not lost on policymakers in Astana, Bishkek, and Tashkent.

Peace as infrastructure

What makes this mineral revolution possible is not just demand in Europe, America and Japan but connectivity. Until the war in Ukraine, most east-west trade routes ran through Russia. Sanctions on Moscow have made that untenable. The Middle Corridor, once a haphazard and secondary route, is now humming and indispensable. The emerging peace deal between Armenia and Azerbaijan is expected to expand the corridor even further, via Armenia to Turkey. For Yerevan, this promises relief from isolation and prospects for economic engagement; for Baku, another outlet westward; for the region, a dramatic cut in transport costs.

What had been a frozen conflict is thawing under the heat of mutual economic interest. Connectivity has become the guarantor of peace, not its hostage. Ports on the Caspian are being upgraded; customs procedures digitized; new rolling stock ordered. What was once an afterthought to Russian railways is becoming a backbone of Eurasian trade. Without it, critical minerals would remain landlocked. With it, Central Asia and the Caucasus can market themselves as a secure bridge between South Asia, China and Europe--a role they have long claimed but never realized.

Shrinking shadows

Russia and China have not disappeared. Moscow still controls key oil pipelines and remittance flows; Beijing remains the biggest creditor in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. But their grip is loosening. Russian strikes on Azerbaijani energy infrastructure, its throttling of Kazakh oil exports, and its disinformation campaigns in Armenia have largely backfired, accelerating the search in regional capitals for alternatives to Moscow. China's economic slowdown and heavy-handed lending terms have made its embrace also less appealing.

The shift is not one of rupture but of balance. The states of the trans-Caspian region will continue to trade with their neighbors. But for the first time since 1991, they are increasingly doing so on their own terms as rising middle powers. President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev of Kazakhstan encapsulates the mood, describing Kazakhstan’s efforts to “play a larger positive role in international relations, bringing balance and building trust.” Behind the sloganeering lies a strategy of diversified growth, international partnerships, and a determination to build on his country’s logistical lock on 80% of all overland transit between Asia and Europe. Then there is its wealth of existing and next-generation extractive resources.

What can the US do?

For outside investors, the opportunity is large but not without obstacles. Infrastructure is developing rapidly, but with some growing pains; rule of law is uneven; politics can be a factor in dealmaking. But the fundamentals are compelling. The region has what the world needs: hydrocarbons for the present, uranium for the transition, and critical minerals for the future. Western governments, eager to secure non-Russian and -Chinese supply chains, have every incentive to back this shift with financing, insurance and diplomatic cover.

2024 B5+1 Forum organized by CIPE in Almaty, Kazakhstan (Source: Flickr)

2024 B5+1 Forum organized by CIPE in Almaty, Kazakhstan (Source: Flickr)

Recent Washington engagements reflect growing interest and confidence in the region—and a strategic bet on its future. Following on the White House peace accord for Armenia and Azerbaijan, the Trump administration has promised development funds for a trans-Caucasus rail line, vital to current trade and future mineral exports. On the outskirts of the U.N. General Assembly, U.S. firms announced over $10 billion in rail, aircraft, tech and manufacturing agreements to expand freight capacity, aviation fleets, and logistical networks. Backed by export credit and development finance, these investments signal a shift towards deeper market-led engagement.

The lesson is simple. Help Central Asia and the Caucasus add value locally, and they will add resilience globally. The alternative--leaving the region as a quarry for China or a hostage to Russia--would be both shortsighted and strategically foolish. The November 6 summit comes at a critical moment: celebrating ten years of the C5+1 platform, taking the moment to reflect and recalibrate, and moving forward from cooperation to launch new strategic value-chain partnerships.

The new Great Game

For too long, outsiders framed the region in terms of the "Great Game" of the 19th century or the Cold War of the 20th: small states at the mercy of bigger powers. That lens is out of date. The story now is one of mid-sized countries making pragmatic choices, forging new partnerships, and insisting on fairer deals.

The war in Ukraine, far from freezing Eurasia into blocs, has catalyzed its middle. Moscow's coercion and Beijing's overreach have given Central Asia and the South Caucasus the very thing they long lacked—the will and the means to chart their own course. The new contest is not over who controls them, but over who partners with them. That, finally, is a game they are determined to play on their own terms.

Dr. Eric Rudenshiold served for four wears as the U.S. National Security Council’s Central Asia Director under Presidents Trump and Biden. He is currently a Senior Fellow at the Caspian Policy Center.