China-Turkmenistan Bilateral Relations

Recent Articles

Author: Dante Schulz

03/09/2022

This piece is part of a series by Dante Schulz and CPC’s Senior Fellows that researches the bilateral relationship between China and the 8 Caspian countries. CPC will release one article on each of the countries and publish a volume encompassing all the research after the last article is released.

Turkmenistan remains the Caspian region’s most isolated country, adhering to a policy of non-interference and non-alignment called "positive neutrality" since it gained independence from the Soviet Union under President Saparmurat Niyazov.[i] His successor, President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, has continued the isolationist policy, maintaining stringent control on the inflow of foreign tourists, religious expression, and freedom of speech.

Despite best efforts at isolation, Turkmenistan is still prone to external shocks. Ashgabat has long maintained lines of communication with the Taliban leadership to prevent conflict along its shared border with Afghanistan. Turkmenistan also wants to revive stalled projects, such as TAPI, with Taliban support.[ii] Moreover, depressed hydrocarbon prices from 2014 through the first waves of the global COVID-19 pandemic dealt a blow to Turkmenistan’s economy.[iii] This led to the adoption of an "import substitution" economic policy.

Turkmenistan has begun to tweak its isolationist policy by reinvigorating economic relations with regional partners, including Turkey and China. Turkmenistan and Turkey sealed eight deals in November 2021 to increase their bilateral trade volume and foster cooperation in multiple sectors.[iv] Turkmenistan has also broadened its diplomatic presence in China. In 2018, Turkmenistan opened its first visa center in China to process applications for a growing number of Chinese tourists to the country, an aspect of Turkmenistan-China relations on which Ashgabat hopes to capitalize.[v]

China and Turkmenistan established diplomatic relations in January 1992, after the Soviet Union collapsed.[vi] In 2006, former President Niyazov traveled to China, beginning an era of closer Turkmenistan-China bilateral relations.[vii] This led directly to the construction of the Central Asia-China natural gas pipelines (Lines A, B, and C), which starting in 2009 began delivering up to 35 billion cubic meters of gas per year to China, and which today account for the lion's share of Turkmenistan's foreign exchange earnings. Ashgabat elevated its relationship with China in 2014 to a strategic partnership, joining the other four Central Asian republics that share this status with China.[viii] Even though Turkmenistan is neither a member of China’s Asian International Investment Bank (AIIB) nor an official participatory country in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Turkmenistan still benefits from its strategic relationship with China.

Turkmenistan President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov and Chinese President Xi Jinping meet during a signing ceremony in Beijing in May 2014. (Radio Free Asia)

Economic Relations

Natural gas exports to China from Turkmenistan are a vital component of the China-Turkmenistan bilateral relationship. China is the world’s largest energy consumer and a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. In an effort to attain its carbon-neutral target by 2060, China seeks to secure stable supplies of natural gas to support its transition from coal to renewable energy resources.[ix] As of 2021, Turkmenistan counted 19.5 trillion cubic meters of natural gas reserves, making it the fourth-largest natural gas repository in the world, and accounting for 9.8 percent of global natural gas reserves.[x] China hopes to tap further into Turkmenistan’s vast natural gas reserves to sustain its economic growth and displace coal by adding a fourth line, Line D, to the existing three pipelines, which would increase deliveries by up to 30 billion cubic meters per year.

Since opening, the Central Asia-China gas pipeline has transported 8.4 trillion cubic feet of natural gas to China.[xi] The 2,277-mile-long set of three pipelines extends from the Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan border to Khorgos on the Kazakhstan-China border, where it connects to China's domestic pipeline network. Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan have also connected their domestic pipeline networks to the Central Asia-China gas pipeline to increase outflows of natural gas from the region to China.[xii]

The Central Asia-China Pipeline (3) transports a majority of Turkmen’s natural gas exports to China each year. Line D of the pipeline (4) is slated to run from Turkmenistan to China via Tajikistan but has been stalled due to complications. (Financial Times)

The Central Asia-China Pipeline (3) transports a majority of Turkmen’s natural gas exports to China each year. Line D of the pipeline (4) is slated to run from Turkmenistan to China via Tajikistan but has been stalled due to complications. (Financial Times)

The China-Turkmenistan relationship has continued to develop around China’s need for natural gas supplies. In August 2021, China’s state energy firm CNPC negotiated payment-in-kind over three years of 17 billion cubic meters of gas from Turkmenistan as compensation in return for drilling three new wells in the Galkynysh field.[xiii],[xiv],[xv] This agreement further supports China as Turkmenistan’s main market for natural gas exports. Turkmenistan is China’s second-largest supplier of natural gas, following only Australia. However, due to soured relations with Australia, China might wish to strengthen its relationship with Turkmenistan to acquire increased access to its natural gas reserves.

China’s state-owned China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) has operated under an on-shore production-sharing agreement (PSA) in the Bagtyyarlyk gas field since 2009, the only on-shore PSA Turkmenistan's government has signed. Turkmenistan's decision to hire CNPC's well-drilling subsidiary to work in the Galkynysh gas field marks a deepening of dependence on Chinese expertise.

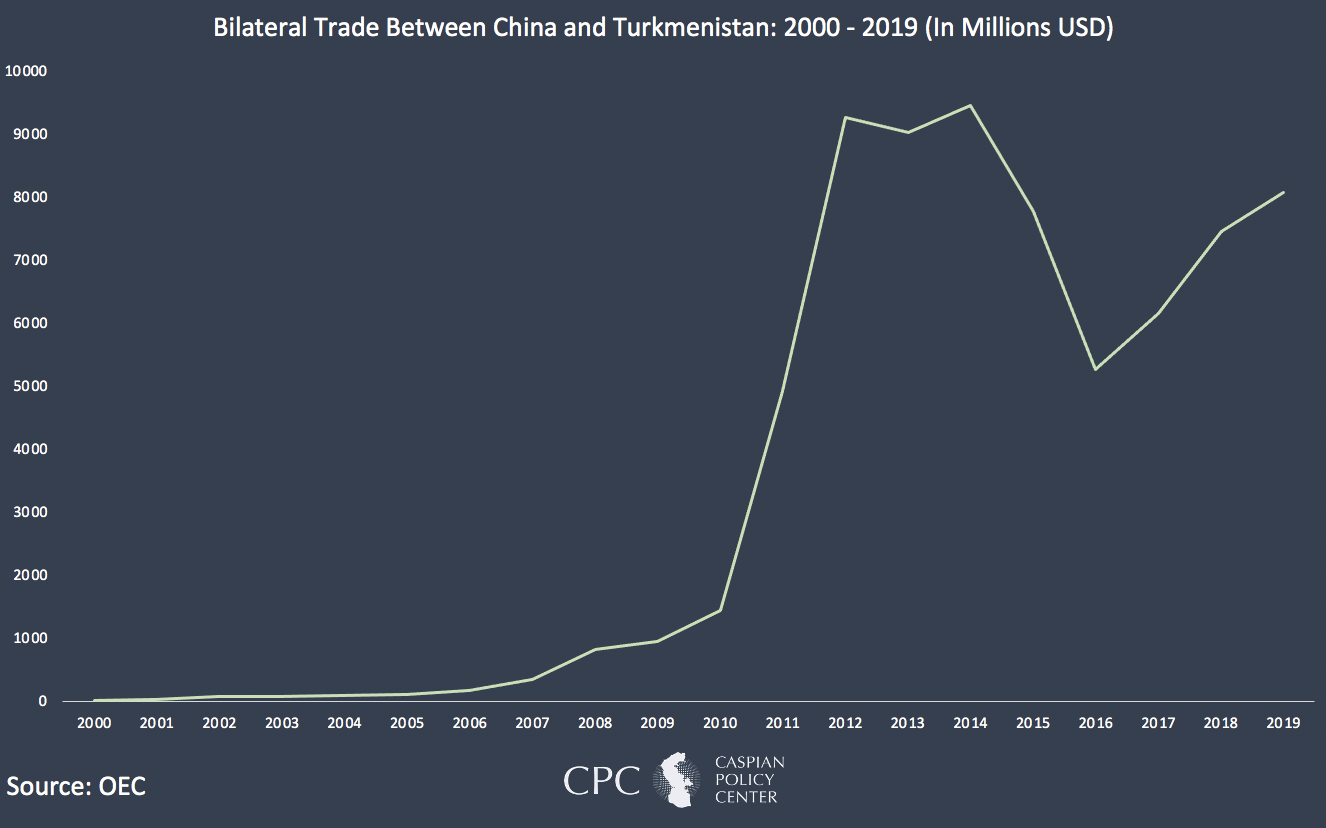

Natural gas has shaped the China-Turkmenistan bilateral relationship to such an extent that Turkmenistan is the only country in the Caspian region not to have a trade deficit with China. In 2019, Turkmenistan exported $7.65 billion worth of goods to China; 99.2 percent of that value was natural gas. On the other hand, Turkmenistan imported only $431 million worth of goods from China that same year. China's $7 billion trade deficit with Turkmenistan in 2019 is a stark difference from the Middle Kingdom's trade relationship with Turkmenistan’s neighboring countries, underscoring Beijing’s appetite for natural gas.[xvi]

Security Relations

Turkmenistan is a non-aligned, neutral country and has rejected calls to accede to the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Chinese-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Chinese military advisors view Turkmenistan’s military capabilities as weak, and there is a precedent of selling military equipment to Ashgabat in exchange for natural gas. Approximately 27 percent of Turkmenistan’s foreign military defense equipment purchases are from China, the second-largest supplier following only Turkey.[xvii]

China was becoming a serious contender for influence by increasing its arms sales to Turkmenistan.[xviii] However, China placed Turkmenistan on a military arms sales blacklist in January 2019 following a severe drop in Turkmen gas exports to China, which subsequently led to a significant rise in China's domestic natural gas price.[xix] This harmed relations between Ashgabat and Beijing and severed the deal brokered between the two countries to pay for arms equipment with natural gas exports.[xx] In accordance with Turkmenistan’s neutrality policy, it has focused on guaranteeing security relations through relations with multiple partners. Turkey has supplied $407 million worth of arms sales to Turkmenistan since 1991, compared with $370 million from Russia and $234 million from China.[xxi]

Conclusion

Turkmenistan has established a strong connection with China by selling its natural gas to an eager consumer. To remain truly neutral and independent, Ashgabat should expand its natural gas partnerships beyond China. In January 2021, Turkmenistan exported 2.786 bcm of natural gas to China, accounting for about 60 percent of its pipeline gas supplies. While the trade relationship between the two countries remains lucrative, Turkmenistan is heavily reliant on a sole purchaser for its main commodity, leaving its economy vulnerable to external shocks. A 30-bcma Trans-Caspian Pipeline appeared to be a viable option for many years, but a myriad of political and financing disagreements coupled with Europe's policy shift to renewable energy undercuts the likelihood of its implementation,[xxii] especially when accounting for the high cost of developing hydrocarbon projects and reluctance of lenders to finance them as governments strive for carbon neutrality.

Ashgabat should also promote its regional connectivity plans. Turkmenistan is a participant in the Ashgabat Agreement, a multimodal international transport agreement linking Central Asia and the Persian Gulf. The 2011 agreement compliments the International North-South Transit Corridor (INSTC), a 13-country force agreement to construct a transport corridor from Mumbai to Saint Petersburg via the Caspian region. Turkmenistan lies on a segment of the Ashgabat Agreement route and opened the Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran (KTI) railway in December 2014.[xxiii] Even so, progress on the INSTC has been slow, and its western corridor was just operationalized in June 2021.[xxiv] Turkmenistan is also collaborating with regional partners to institute the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Tajikistan railway and the Afghanistan-Turkmenistan-Azerbaijan-Georgia-Turkey transport corridor. Turkmenistan’s regional connectivity ambitions correspond with China’s overland trade route aspirations.

Last, Turkmenistan should seek ways to reinvest profits acquired from natural gas exports into infrastructure development. Turkmenistan is situated at the crossroads of numerous proposed international transit routes. Investing in infrastructure development, including high-speed rail and well-maintained highways, would ensure that Turkmenistan is connected to regional routes and would allow Turkmen commodities to be transported to additional markets. Turkmenistan could simply allocate to this end the profits accrued from exports to China of its natural gas.

[i] Stronski, P. (2017, January 30). Turkmenistan at Twenty-Five: The High Price of Authoritarianism. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2017/01/30/turkmenistan-at-twenty-five-high-price-of-authoritarianism-pub-67839.

[ii] Schulz, D. (2021, September 8). Turkmenistan’s Deviated Approach to the Taliban Explained. Caspian Policy Center. https://www.caspianpolicy.org/research/security-and-politics-program-spp/turkmenistans-deviated-approach-to-the-taliban-explained-13229.

[iii] Pannier, B. (2020, April 23). Plunge In Oil Prices Deals Another Blow To Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan. Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/qishloq-ovozi-plunging-oil-prices-kazakhstan-turkmenistan-economic-problems/30572905.html.

[iv] (2021, November 27). Turkey, Turkmenistan sign deals, strengthen ties in Erdogan’s visit. Daily Sabah. https://www.dailysabah.com/business/economy/turkey-turkmenistan-sign-deals-strengthen-ties-in-erdogans-visit.

[v] Yiran, Z. (2018, July 20). Turkmenistan opens first China visa center. China Daily. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201807/20/WS5b517e70a310796df4df7b29.html.

[vi] (2013, September 2). China-Turkmenistan ties becoming strategic. China Daily. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013xivisitcenterasia/2013-09/02/content_16936006.htm.

[vii] Ovezdyrdyyev, K. & Zhang, B. (2020, January). Research on Economic and Trade Cooperation Problems and Countermeasures between China and Turkmenistan. Open Journal of Business and Management. https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation.aspx?paperid=97881.

[viii] Kucera, J. (2014, May 13). With Turkmenistan, China Now Has “Strategic Partnerships” With All Five Central Asian States. Eurasianet. https://eurasianet.org/with-turkmenistan-china-now-has-strategic-partnerships-with-all-five-central-asian-states.

[ix] (2021, June 24). China to use more natural gas in energy mix to 2035 – CNPC. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/china-use-more-natural-gas-energy-mix-2035-cnpc-2021-06-24/.

[x] Fawthrop, Andrew (2021, March 15) Profiling the top five countries with the biggest natural gas reserves. NS Energy. https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/features/biggest-natural-gas-reserves-countries/

[xi] Zhang, R. (2021, May 12). China looks to Turkmenistan for more gas as it cuts Australian supplies. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3133084/china-looks-turkmenistan-more-gas-it-cuts-australian-supplies.

[xii] Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline, Turkmenistan to China. Hydrocarbons Technology. https://www.hydrocarbons-technology.com/projects/centralasiachinagasp/.

[xiii] (2021, August 24). China’s CNPC secures more Turkmen gas in new deal – source. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/chinas-cnpc-secures-51-bcm-turkmen-gas-new-deal-says-source-2021-08-23/.

[xiv] Компания из КНР выиграла тендер на бурение новых скважин на самом крупном газовом месторождении Туркменистана" (in Russian). Turkmenistan.ru. 20 June 2021.

[xv] Svintsova, Ye. (2021 August 24). Китайская компания пробурит 3 газовых скважины в Туркменистане (in Russian). Neftegaz.RU.

[xvi] OEC. Turkmenistan/China. https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/tkm.

[xvii] Sukhankin, S. (2020, October 19). The Security Component of the BRI in Central Asia, Part Three: China’s (Para)Military Efforts to Promote Security in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The Jamestown Foundation. https://jamestown.org/program/the-security-component-of-the-bri-in-central-asia-part-three-chinas-paramilitary-efforts-to-promote-security-in-kazakhstan-uzbekistan-and-turkmenistan/.

[xviii] Rozanskij, V. (2021, July 21). China’s economic dominance in Central Asia grows. Asia News. http://www.asianews.it/news-en/China%27s-economic-dominance-in-Central-Asia-grows-53693.html.

[xix] Yan, Y, T. (2019, September 11). What Drives Chinese Arms Sales in Central Asia. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2019/09/what-drives-chinese-arms-sales-in-central-asia/.

[xx] Jardine, B. & Lemon, E. (2020, May). In Russia’s Shadow: China’s Rising Security Presence in Central Asia. Kennan Cable (52). https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/kennan-cable-no-52-russias-shadow-chinas-rising-security-presence-central-asia.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Stein, D. D. (2020, August 20). Trans-Caspian Pipeline–Still a pipe dream? Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/energysource/trans-caspian-pipeline-still-a-pipe-dream/.

[xxiii] Contessi, N. P. (2020, March 3). In the Shadow of the Belt and Road. Reconnecting Asia. https://reconasia.csis.org/shadow-belt-and-road/.

[xxiv] Bhardwaj N. (2021, June 25). India’s Export Opportunities Along the International North South Transport Corridor. India Briefing. https://www.india-briefing.com/news/indias-export-opportunities-along-the-international-north-south-transport-corridor-22412.html/.