The Ukraine Deal Is Just the Start—Central Asia Holds the Key to U.S. Mineral Security

Recent Articles

Author: Joshua Bernard-Pearl

06/04/2025

The United States has signed a new mineral deal with Ukraine to ensure U.S. access to strategic minerals while funding Ukraine's reconstruction efforts and its ability to resist Russian aggression. These minerals are crucial for nearly every facet of the U.S. high-tech economy—from smartphones to wind turbines to fighter jets—yet Washington has largely relied on Beijing for its supply of refined materials. While the Ukraine mineral deal is a great start, the U.S. will need more sources to meet its immense and growing demand, as well as to address supply chain vulnerabilities. Central Asia and the South Caucasus could fill this gap in demand while simultaneously working to grant these same nations a measure of strategic autonomy away from Russia and China.

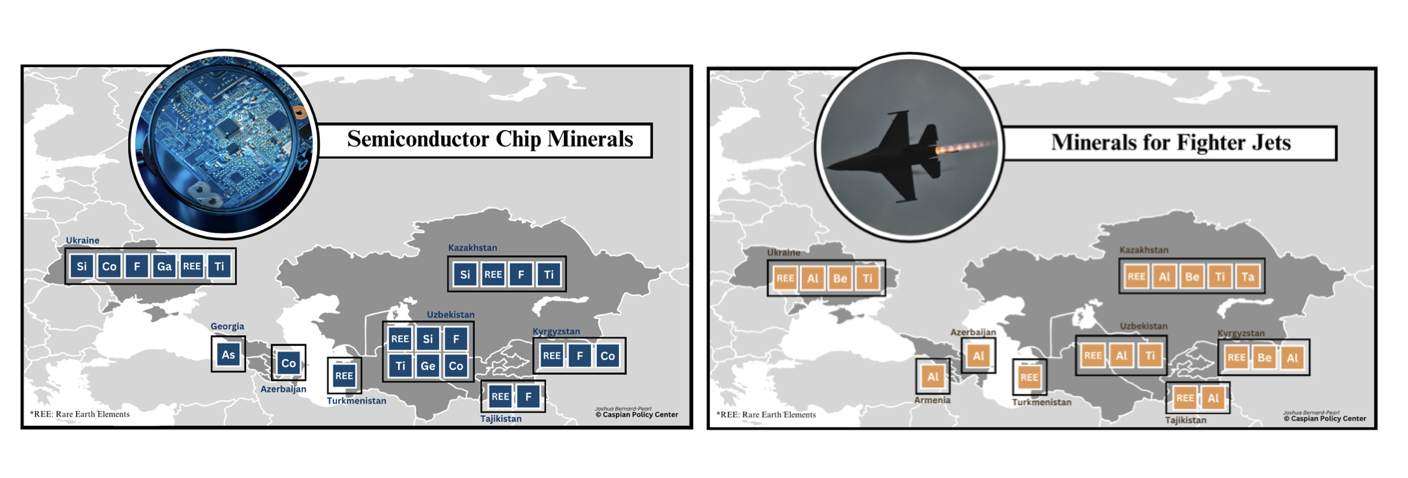

The Caspian Policy Center’s recent report, A Guide for Policymakers: How to Meet U.S. Strategic Mineral Needs, highlights what minerals are present in Ukraine, Central Asia, and the South Caucasus, as well as what they are used for and how to obtain them.

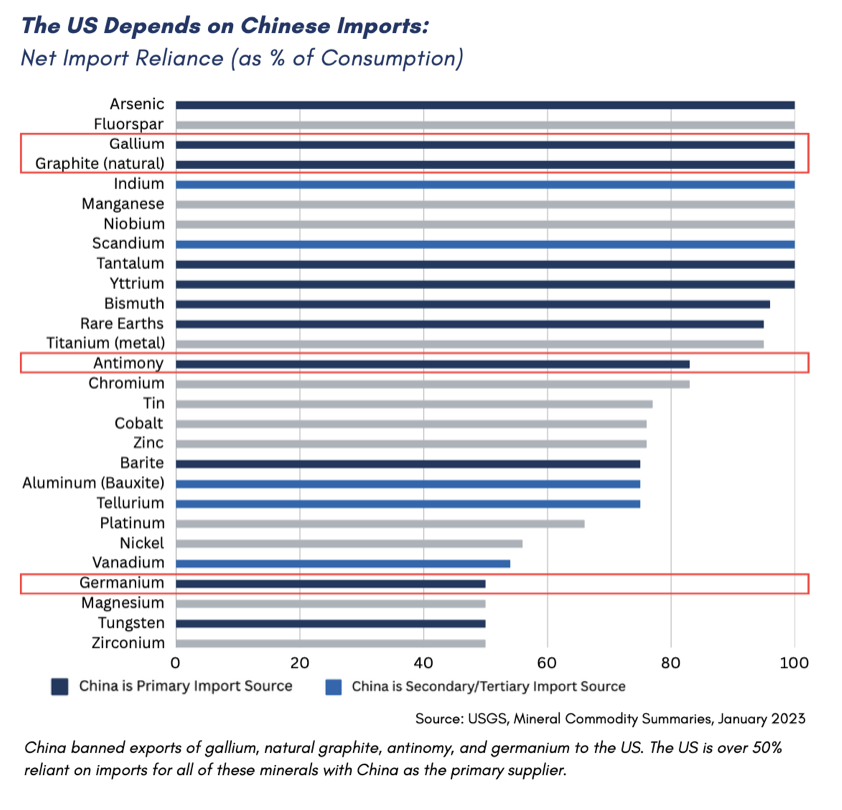

The need for alternative sources of critical minerals is clear. The United States has long relied on Chinese mining and refining for the vast majority of its critical minerals, granting Beijing an economic cudgel over the American economy. Seeing American vulnerability, China banned the export of several key minerals to the U.S., including gallium, graphite, germanium, and antimony. More recently, U.S. tariffs on China have made these minerals increasingly expensive. In retaliation, China introduced new export restrictions, including on rare earth elements. The Ukraine mineral deal, in addition to another potential deal under discussion with the Democratic Republic of Congo, highlight an increased sense of urgency on this issue within the U.S. government and foreshadows a pattern of mineral diplomacy in this administration.

The need for alternative sources of critical minerals is clear. The United States has long relied on Chinese mining and refining for the vast majority of its critical minerals, granting Beijing an economic cudgel over the American economy. Seeing American vulnerability, China banned the export of several key minerals to the U.S., including gallium, graphite, germanium, and antimony. More recently, U.S. tariffs on China have made these minerals increasingly expensive. In retaliation, China introduced new export restrictions, including on rare earth elements. The Ukraine mineral deal, in addition to another potential deal under discussion with the Democratic Republic of Congo, highlight an increased sense of urgency on this issue within the U.S. government and foreshadows a pattern of mineral diplomacy in this administration.

Central Asia is rich in minerals, with established mines already operational. This contrasts with Ukraine, which—despite vast mineral wealth—has comparatively fewer operational ventures and less mineral infrastructure. This task is further complicated by the ongoing war and uncertainty of territorial control. Investors are wary of building new infrastructure in Ukraine when it could be destroyed by a Russian drone at a moment's notice, captured by the Russian military, or face delays and lawsuits related to worker safety. Moreover, many of Ukraine's most valuable deposits currently lie behind Russian lines, including a significant lithium deposit and three rare earth deposits in Zaporizhzhya. Regardless of these challenges, Ukraine will not be able to address U.S. mineral demands with new mining operations for years to come. It takes up to 18 years and $500 million to $1 billion to construct a mine and separation facility.

Central Asia and the Caucasus can meet U.S. demand now, while Ukraine's mine capacity is being built up. This comes with the bonus of increasing U.S. geopolitical influence in a region sensitive to both Russia and China. Moreover, Central Asia contains additional minerals not found in Ukraine in significant quantities. This includes chromium production in Kazakhstan, ranked as the second largest global producer with the world's largest reserves and the capacity to expand further. Tajikistan is currently the world's second largest producer of antimony, while Kyrgyzstan holds the fourth largest reserves. Kazakhstan is also the world’s fourth largest producer of barite but does not export a significant quantity of it to the U.S. yet. The whole region is abundant in rare earth elements, with existing initiatives to increase their extraction. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan lead the charge, containing the most deposits.

Investment into Central Asia should focus on the next level of the supply chain: refining. China currently dominates this stage, making up 85% of refining capabilities. A U.S.–Central Asia mineral deal could build off a Ukraine-deal-style framework and include U.S. investments into processing plants in return for offtake agreements. Refining these elements at their source would result in cheaper products for the U.S. and increased revenue for Central Asia at the expense of China. The U.S. would get the minerals it needs with less reliance on China. The region would gain increased economic independence from Chinese control of the supply chain, affording it more geostrategic autonomy to work with the U.S. in the future.

Investment into Central Asia should focus on the next level of the supply chain: refining. China currently dominates this stage, making up 85% of refining capabilities. A U.S.–Central Asia mineral deal could build off a Ukraine-deal-style framework and include U.S. investments into processing plants in return for offtake agreements. Refining these elements at their source would result in cheaper products for the U.S. and increased revenue for Central Asia at the expense of China. The U.S. would get the minerals it needs with less reliance on China. The region would gain increased economic independence from Chinese control of the supply chain, affording it more geostrategic autonomy to work with the U.S. in the future.

The U.S.-Ukraine mineral investment deal is a crucial step toward ensuring Washington’s future supply of strategic minerals. Central Asia could be a key part of this safety net too, requiring less investment and delivering quicker returns as Ukraine builds and rebuilds its mining and processing capacity. The U.S. government can build on its momentum from the Ukraine deal to expand mineral diplomacy and establish a robust, geopolitically advantageous network of critical mineral supply chains in Central Asia.