China-Kazakhstan Bilateral Relations

Recent Articles

Author: Dante Schulz

02/17/2022

This piece is part of a series by Dante Schulz and CPC’s Senior Fellows that researches the bilateral relationship between China and the 8 Caspian countries. CPC will release one article on each of the countries and publish a volume encompassing all the research after the last article is released.

Kazakhstan shares a 1,108-mile-long border with China, making the country a key western neighbor for China and China an immediate factor for Kazakhstan’s security and well-being. Overall official relations have been good. The two countries were able to delineate the border two years after establishing diplomatic relations in 1992.[i] Moreover, the two have continued to engage in numerous efforts, including buttressing regional security with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), promoting a regional economic development vision via Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and advancing regional connectivity.

China was among the first stops abroad for Kazakhstani President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev after he took office in March 2019, attesting to his commitment to advance bilateral relations.[ii] In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping unveiled his Belt and Road Initiative during a state visit in Nur-Sultan. In President Xi’s speech at Nazarbayev University, he emphasized the importance of Kazakhstan in China’s energy portfolio and mining sourcing.[iii] Furthermore, many of the proposed overland transit routes to link China with European markets traverse Kazakhstan.

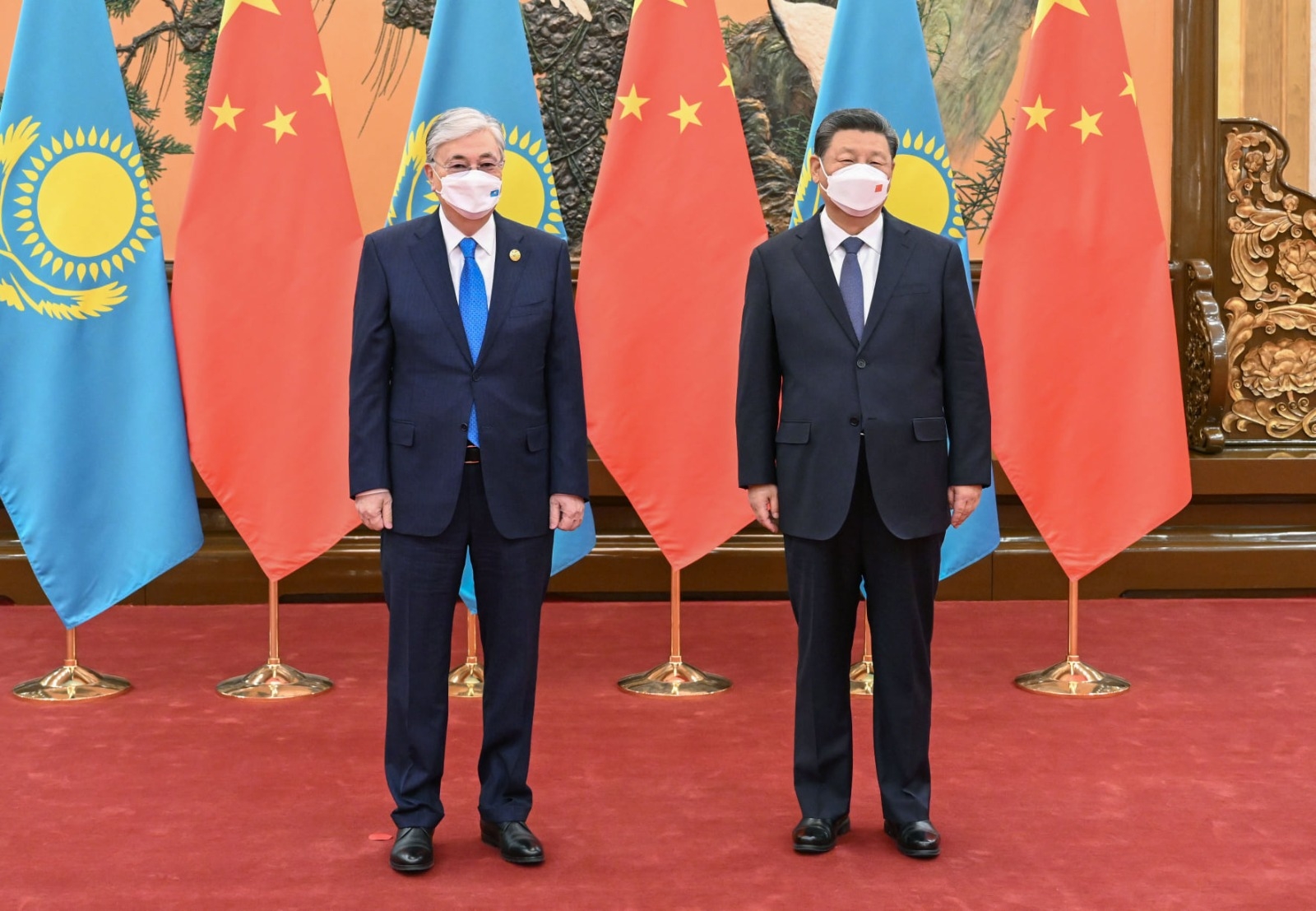

Kazakhstani President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev and Chinese President Xi Jinping met in Beijing during the 2022 Winter Olympics. (Kazakhstan presidential administration)

Kazakhstani President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev and Chinese President Xi Jinping met in Beijing during the 2022 Winter Olympics. (Kazakhstan presidential administration)

China, especially with its growing influence in the region, is a prime element in Kazakhstan’s multi-vector foreign policy. Under this policy, Nur-Sultan actively engages China, Russia, Turkey, the European Union, the United States, and other actors to ensure it avoids falling dependent on any one major power. As part of this approach, Kazakhstan enjoys member status in the United Nations, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the Organization of Turkic States (OTS), the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), as well as in the Shanghai Cooperation organization.[iv] Kazakhstan’s burgeoning relationship with China will be important, but will be one piece of the network of relations it has developed with other partners.

Kazakhstan is a critical segment to China’s overland trade route ambitions and is a fruitful destination for Chinese investors. However, local grumblings towards perceived Chinese encroachment, as well as regarding the treatment of Uyghurs, are complicating factors in the relationship even as Kazakhstan’s government has been keen to stamp out any public displays of disaffection with China.

Economic Relations

Called the buckle in the Belt and Road Initiative, Kazakhstan’s geographical location and close economic ties make it a linchpin for China’s overland economic ambitions. Kazakhstan joined the BRI in 2013 shortly after its unveiling in Nur-Sultan.[v] Kazakhstan then became an Asian International Investment Bank (AIIB) signatory in 2014, further solidifying economic links with its eastern neighbor and opening channels to receive lucrative Chinese investment opportunities.[vi] There are currently 21 BRI projects underway in Kazakhstan, totaling $12.07 billion. China is among the top five largest foreign investors in Kazakhstan. The approximately 700 joint Kazakhstani-Chinese enterprises, comprise 4.7 percent of total investment in the country.[vii]

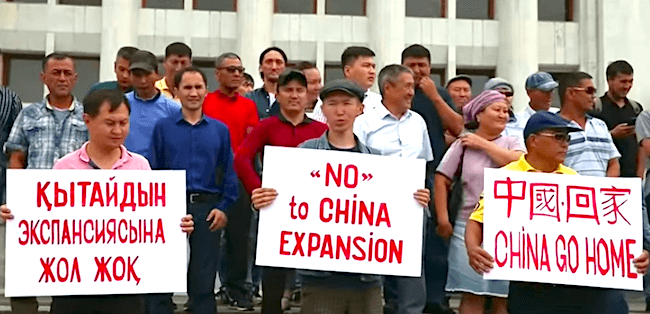

Anti-Chinese protests are becoming more commonplace in Kazakhstan as disgruntled residents rally against Chinese-financed projects. (Reuters/Pavel Mikheyev)

Anti-Chinese protests are becoming more commonplace in Kazakhstan as disgruntled residents rally against Chinese-financed projects. (Reuters/Pavel Mikheyev)

Central to Chinese investment in Kazakhstan are two transport crossings: Khorgos and Dostyk-Alashankou. The Khorgos Gateway is slated to be the world’s largest dry port with projections estimating that it will be able to handle 30 million tons of freight a year.[viii] In addition to the dry port, Kazakhstan hopes to inaugurate a free-trade border zone in Khorgos to facilitate trade with China and boost jobs. Both governments hope that economic activity will increase the city’s population to more than 100,000 people.[ix]

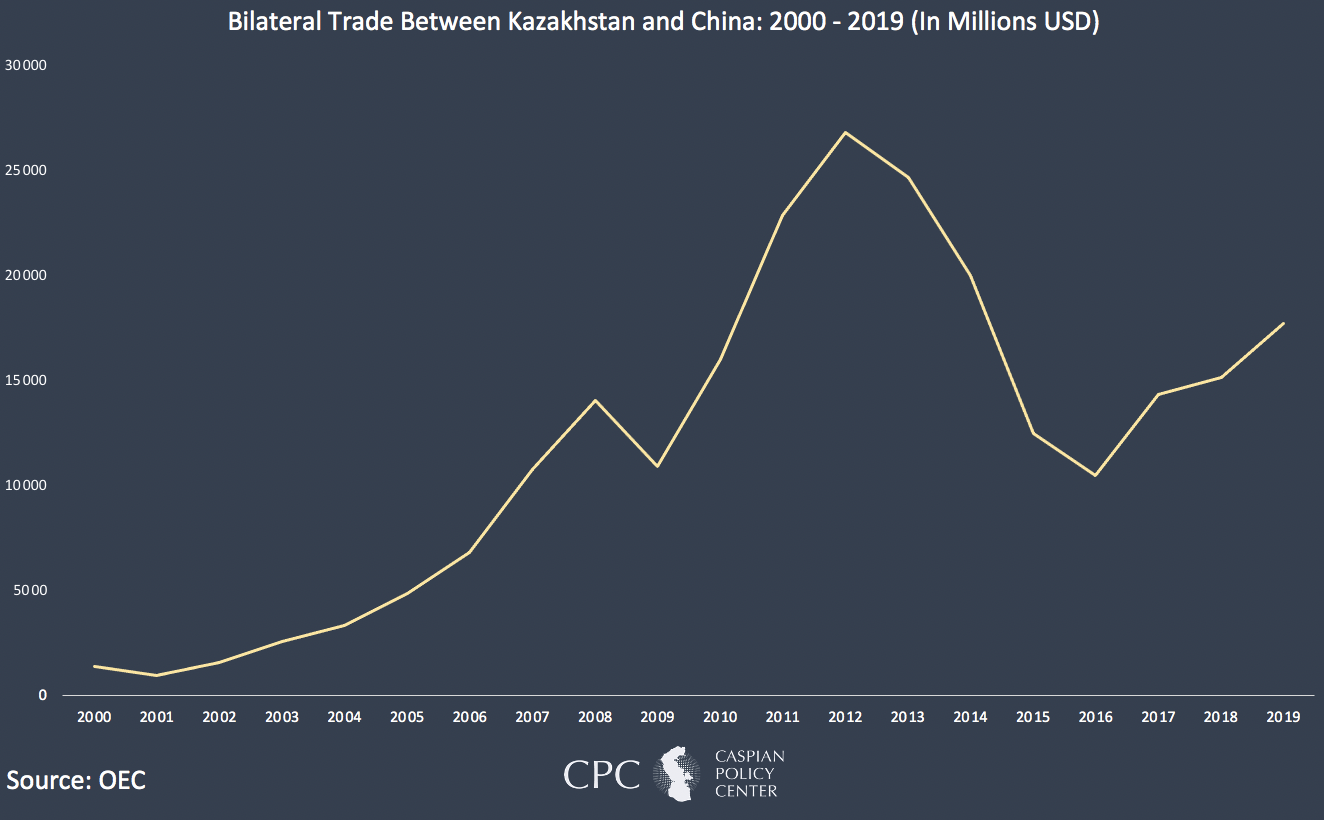

Bilateral trade between Kazakhstan and China has skyrocketed due to the improvement in overland transit routes spurred by BRI and AIIB financing initiatives. In 2019, Kazakhstan’s exports to China totaled $7.92 billion, making China Kazakhstan’s largest trading partner. In the same year, imports from China were worth $9.8 billion. Kazakhstan rose to become China’s 40th largest trading partner worldwide. Kazakhstan is China’s second-largest trading partner in the region, after Turkmenistan.[x]

Even with the increase in bilateral investment and trade, Khorgos has exposed underlying issues with the BRI. Rail transport composes only a fraction of preferred global transit routes; most rely on sea routes, which are cheaper. Moreover, many of the cargo trains returning from Europe to China via Kazakhstan are empty because China subsidizes these trips as well as because of the overall imbalance of China’s trade with the rest of the world.[xi] The realization of numerous drawbacks of Chinese-financed BRI projects could dissuade Kazakhstan and other regional governments from further engaging with China. Therefore, revenue generated from its profitable hydrocarbon sector could allow Nur-Sultan to attract alternative sources for project financing by cooperating with other trading partners.

Security Relations

China introduced its New Diplomacy initiative in the early 2000’s, comprised of the New Security Concept, the New Development Approach, and the New Civilization Outlook. The New Security Concept advocates that countries formulate multilateral approaches to regional security issues.[xii] China has employed its New Security Concept in the Caspian region with Kazakhstan as a principal partner. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization was founded in 2001 from the original members of the Shanghai Five (China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan). Since then, Uzbekistan, India, and Pakistan have acceded to the SCO.[xiii] The SCO aims to maintain stability in the region, strengthen alliances among member states, and promote cooperation in culture, politics, trade, energy, and research.[xiv]

As a founding member of the SCO, Kazakhstan utilizes the multilateral format to conduct anti-drug operations, combat terrorism and extremism, and partake in joint health and agricultural initiatives. Kazakhstan has introduced border security strategies and supported the SCO’s food security network. Kazakhstan’s President Tokayev said that the SCO is “rightfully regarded as an effective tool for strengthening cooperation and trust in an area covering a quarter of the planet’s territory, 40 percent of the world’s population, and a third of the world’s GDP…” showcasing Kazakhstan’s support for the Chinese-led SCO.[xv]

The return of the Taliban in Afghanistan following the U.S. troop withdrawal from the country in August 2021 has added to the value of the SCO. President Xi uses China’s clout in the organization to promote regional strategies in the face of the ongoing turmoil in Afghanistan.[xvi] While China has avoided direct involvement in Afghanistan, it is manipulating the situation politically to advance its security position in the region. Kazakhstan could become a prime focus for Beijing in expanding its security interests in the Caspian region.

At the same time, and as the January events in Kazakhstan showed, despite Chinese efforts to forge a consolidated security pact in Central Asia, Kazakhstan is still linked to Russia when it comes to security interests. Kazakhstan is an active member of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization, which also includes Belarus, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. It was the CSTO that temporarily provided security forces to help restore order in January 2022 in Kazakhstan. Moscow is also using the conflict in Afghanistan to flex its military and political influence in the region and to show China that it still maintains significant sway in the region. President Tokayev spoke of the urgent need to muster a regional force to manage the aftermath of the Taliban resurgence in Afghanistan with CSTO assistance.[xvii]

Local Reactions to Chinese Involvement

Anti-Chinese sentiment reached a boiling point in April 2016 when thousands of protesters gathered to oppose amendments to Kazakhstan’s Land Code. The change would have allowed foreigners to rent agricultural plots in Kazakhstan for 25 years. Many Kazakhstanis, concerned that Chinese investors would quickly buy up much of Kazakhstan’s agricultural land, took to the streets to demand that the change be repealed.[xviii]

Rising Sinophobia and growing resentment towards Chinese investors have continued to smolder for several years, damaging Chinese trust. In September 2019, the number of protesters rallying against Chinese economic projects in Kazakhstan soared in several cities, including Aktobe, Almaty, Shymkent, and Nur-Sultan.[xix] Approximately 50 people were detained in the country’s two largest cities.[xx] Nur-Sultan responded to protesters in 2019 by releasing data uncovering that 55 Kazakhstani projects were receiving Chinese investment and loans through BRI channels, amounting to $27.6 billion. About half of this financing is funneled into oil and natural gas projects.[xxi] Many opposed to Chinese projects in the country still feel that Chinese investors will be able to use their economic prowess to sway domestic decisions in favor of Beijing.

Reports of mass detentions of ethnic Uyghurs and other Muslim minority ethnic groups in China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region have affected relations with Kazakhstan and other Central Asian republics. Dubbed re-education camps by the Chinese government, those who have been released or escaped the camps have reported instances of forced sterilization, torture, and indoctrination.[xxii] Human rights groups say about 380 facilities exist in Xinjiang, incarcerating about one million people, including ethnic Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and Uzbeks.[xxiii] Refugees and activists who have experienced the situation firsthand have gone public in Kazakhstan, detailing their accounts.[xxiv] Kazakhstan has the largest Uyghur diaspora community, and ethnic Kazakhs constitute the second-largest group interned in Xinjiang, fueling campaigns to take action in Xinjiang.[xxv]

Kazakhstan’s close economic ties with China have prompted Nur-Sultan to stifle activists focused on Xinjiang issues. Kazakhstan has ordered organizations dedicated to the Uyghur plight to shut down and arrested activists present at protests under the guise of violating COVID-19 quarantine restrictions.[xxvi] Moreover, Kazakhstan’s swift crackdown on Uyghur activists contradicts its qandas strategy.[xxvii] Previously referred to as oralmans, thousands of ethnic Kazakhs were repatriated from across other Central Asian states to Kazakhstan under a policy instituted by the Kazakhstani government. Most recently, more than 250 ethnic Kazakhs were resettled in Kazakhstan from Turkmenistan.[xxviii] However, the policy does not seem to be so objective for ethnic Kazakhs arriving from China. An ethnic Kazakh woman holding Chinese citizenship, Sayragul Sauytbay, was not granted asylum by Nur-Sultan and, instead, was resettled in Sweden.[xxix]

Policy Recommendations

Kazakhstan is the linchpin to China’s BRI ambitions. Its vast territory and connections with Russia, the other Central Asian republics, and the Caspian Sea have highlighted Kazakhstan’s importance for China. Kazakhstan has also had ambitions to join the club of modern, developed economies and to play a more prominent role on the world stage. Given this situation and set of goals, Nur-Sultan should further diversify trading partners. Kazakhstan’s multi-vector foreign policy is lauded for shifting Kazakhstan from a country dependent on a single regional power to one that can balance the interests of multiple powers to realize its own foreign policy ambitions. China is Kazakhstan’s largest trading partner and a significant source of foreign direct investment. An over-reliance on Chinese capital could have detrimental impacts to Kazakhstan’s economy if Beijing chooses to reduce its economic engagement. Pursuing economic and other reforms outlined in President Tokayev’s speech to the Parliament following the January violence would aid in this economic diversification by making Kazakhstan more attractive to other foreign business partners.

In addition, Kazakhstan should standardize its application of its qandas policy. The qandas policy of repatriating ethnic Kazakhs from other countries is not evenly applied. Ethnic Kazakhs seeking resettlement in Kazakhstan from China often face additional legal and social hurdles that inhibit them from properly finding a home in the country. Kazakhstan should reaffirm its qandas policy to make it uniform for ethnic Kazakhs from all countries, including China. Continued uneven application of its policy could further fuel anti-Chinese sentiments in Kazakhstan.

Lastly, Nur-Sultan should consider continuing development of the Khorgos special economic zone. Khorgos has the capacity to house over 100,000 residents and serve as a base of operations for Chinese investors and others moving into the Central Asian market. While Kazakhstan should continue to urge Chinese investors to consider transitioning affairs to Khorgos, it should seek to attract logistics and other companies from elsewhere in the world to the city to make it a center for value-added economic actives as well as a transit hub on the new silk road. By demonstrating increased business output from the Khorgos special economic zone, it can attract other investors from the West, including the United States to engage in the Central Asian country.

[i] Le Corre, P. (2019, February 28). Kazakhs Wary of Chinese Embrace as BRI Gathers Steam. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/02/28/kazakhs-wary-of-chinese-embrace-as-bri-gathers-steam-pub-78545.

[ii] Karin, E. (2021, July 18). China-Kazakhstan relations will open a new chapter in history. China Global Television Network. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-07-18/China-Kazakhstan-relations-will-open-a-new-chapter-in-history-11Zzo9GgjKg/index.html.

[iii] Wasserman, P. (2019, March 26). Between a Bear and a Dragon: New challenges for Kazakhstan. Global Risk Insights. https://globalriskinsights.com/2019/03/kazakhstan-china-russia-leader/.

[iv] Zhussupova, A. (2021, March 9). Peace Through Engagement: The Multi-Vector Direction of Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy. Astana Times. https://astanatimes.com/2021/03/peace-through-engagement-the-multi-vector-direction-of-kazakhstans-foreign-policy/.

[v] Groening, P. (2020, Spring). Participation in the Belt and Road Initiative: Who Joins and Why? Honors College. 595. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1594&context=honors.

[vi] (2014, October 24). Kazakhstan joins Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank with other 21 nations. AKI Press. https://m.akipress.com/news:550234:Kazakhstan_joins_Asian_Infrastructure_Investment_Bank_with_other_21_nations/.

[vii] Shayakhmetova, Z. (2021, April 29). Positive Dynamics Observed in Trade Between Kazakhstan and China. Astana Times. https://astanatimes.com/2021/04/positive-dynamics-observed-in-trade-between-kazakhstan-and-china/.

[viii] The building of a new Dubai in China. South China Morning Post. https://multimedia.scmp.com/news/china/article/One-Belt-One-Road/khorgos.html.

[ix] Standish, R. (2019, October 1). China’s Past Forward Is Getting Bumpy. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/10/china-belt-road-initiative-problems-kazakhstan/597853/.

[x] OEC. China/Kazakhstan. https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/kaz

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Serikkaliyeva, A., Amirbek, A., & Batmaz, E. S. (2018, Fall). Chinese Institutional Diplomacy toward Kazakhstan: The SCO and the New Silk Road Initiative. Insight Turkey, 20(4), 129-152. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26542177?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents.

[xiii] Battams-Scott, G. (2019, February 26). How Effective Is the SCO as a Tool for Chinese Foreign Policy? E-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2019/02/26/how-effective-is-the-sco-as-a-tool-for-chinese-foreign-policy/.

[xiv] Ali, Y. (2021, June 15). 20 years of Shanghai Cooperation Organization: a View from Kazakhstan. Astana Times. https://astanatimes.com/2021/06/20-years-of-shanghai-cooperation-organization-a-view-from-kazakhstan/.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Woo, R. & Kasolowsky, R. (2021, September 17). China’s Xi says SCO states should help drive smooth Afghan transition. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-xi-says-sco-states-should-help-drive-smooth-afghan-transition-2021-09-17/.

[xvii] (2021, August 24). Kazakh President Takes Part in CSTO Collective Security Council Meeting. Astana Times. https://astanatimes.com/2021/08/kazakh-president-takes-part-in-csto-collective-security-council-meeting/.

[xviii] (2016, April 28). Kazakhstan’s land reform protests explained. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-36163103.

[xix] Mikheyev, P., Vaal, T., Olzhas, A., & Maclean, W. (2019, September 4). Dozens protests against Chinese influence in Kazakhstan. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kazakhstan-china-protests/dozens-protest-against-chinese-influence-in-kazakhstan-idUSKCN1VP1B0.

[xx] Wani, A. (2019, October 4). Rising anti-Chinese sentiments in Kazakhstan. Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/rising-anti-chinese-sentiments-in-kazakhstan/.

[xxi] Magistad, M. K. (2020, September 14). China’s new Silk Road traverses Kazakhstan. But some Kazakhs are skeptical of Chinese influence. The World. https://www.pri.org/stories/2020-09-14/chinas-new-silk-road-traverses-kazakhstan-some-kazakhs-are-skeptical-chinese.

[xxii] Hill, M., Campanale, D., & Gunter, K. (2021, February 2). “Their goal is to destroy everyone”: Uighur camp detainees allege systematic rape. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-55794071.

[xxiii] (2020, September 24). Xinjiang: Large numbers of new detention camps uncovered in report. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-54277430.

[xxiv] Standish, R. (2019, September 3). “Our Government Doesn’t Want to Spoil Relations with China”. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/09/china-xinjiang-uighur-kazakhstan/597106/.

[xxv] Roberts, S. R. (2020, October 23). Kazakhstan’s Ambiguous Position towards the Uyghur Cultural Genocide in China. The Asan Forum. https://theasanforum.org/kazakhstans-ambiguous-position-towards-the-uyghur-cultural-genocide-in-china/.

[xxvi] Standish, R. & Toleukhanova, A. (2021, April 4). Kazakh Activism Against China’s Internment Camps is Broken, But Not Dead. Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakhstan-protests-china-xinjiang-rights-abuses/31186209.html.

[xxvii] Sanayeva, D. (2021, August 18). Why Haven’t Kazakh Xinjiang Protests Gained Traction. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2021/08/why-havent-kazakh-xinjiang-protests-gained-traction/.

[xxviii] (2021, May 23). Hundreds of Ethnic Kazakhs In Turkmenistan Emigrate, Happy to Leave Lives of Poverty, Repression. Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/ethnic-kazakhs-emigrate-turkmenistan-new-life/31269215.html.

[xxix] Kumenov, A. (2019, June 3). Kazakhstan: Xinjiang Kazakh finds haven in Europe. Eurasianet. https://eurasianet.org/kazakhstan-xinjiang-kazakh-finds-haven-in-europe.