U.S. Participation in the December 2010 OSCE Summit in Astana

Recent Articles

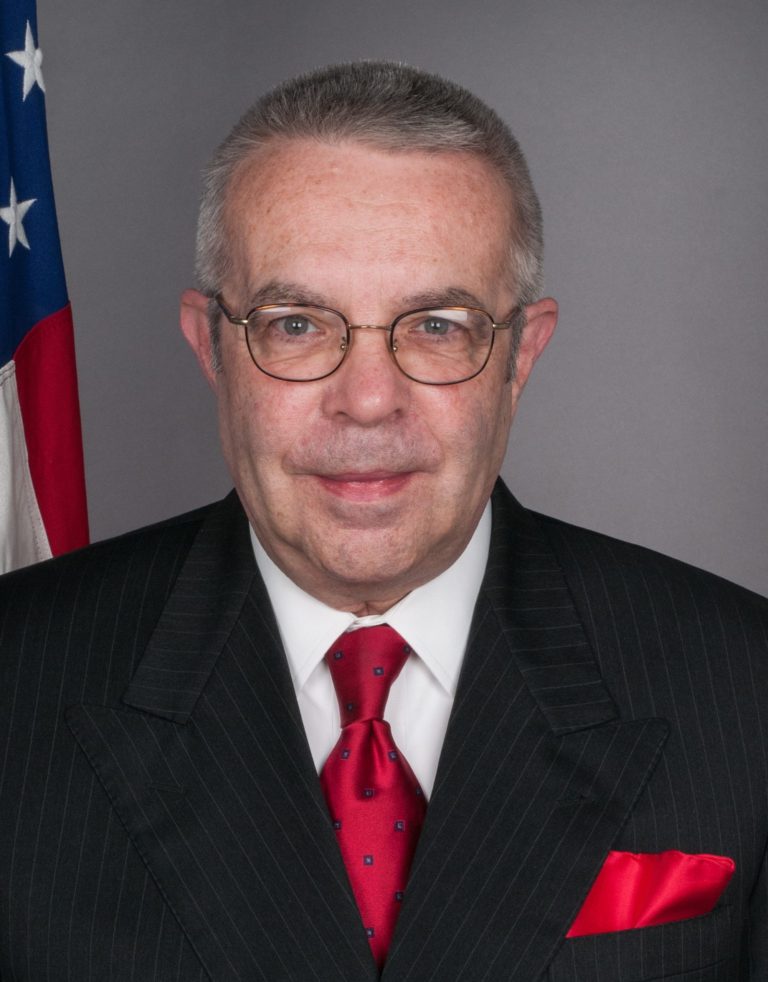

Author: Ambassador (Ret.) Richard E. Hoagland

05/12/2021

Ambassador (Ret.) Richard Hoagland

During my ambassadorship to the Republic of Kazakhstan (2008-2011), the ninth-largest country in the world, two historic events occurred. The first was the final lockdown, under the U.S.-Kazakhstan Cooperative Threat Reduction Program with the collaboration of the U.S. Department of Energy, of enough plutonium and highly enriched uranium from Aktau’s BN-350 high-yield nuclear reactor to have made over 700 nuclear weapons. The second was the first summit of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) ever to take place in a former Soviet republic. Kazakhstan’s exemplary commitment to nuclear non-proliferation has been widely reported, and so I will focus on the OSCE summit because it illustrates some of the behind-the-scenes challenges that diplomats face.

At the independence of the former Soviet Socialist Republics as a result of the fall of the Soviet Union in December 1991, most observers expected that Uzbekistan would emerge as the leading country in Central Asia because of its large population and relatively high level of industrial development. But that didn’t happen because Uzbekistan’s first leader, President Islam Karimov, kept Uzbekistan mired in its Soviet past. Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev, however, undertook fundamental changes from the beginning of his tenure that internationalized his nation. Nearly 20 years later, he was eager to showcase that nation and its real achievements to the world. And when Kazakhstan gained the annually rotating OSCE Chairmanship in 2010, he insisted on hosting in his new capital, Astana, a relatively rare OSCE summit. Such events are a common part of international diplomacy, but this one became controversial in Washington.

During both the George W. Bush and Barack Obama presidential administrations, the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (DRL) played a prominent role in U.S. foreign policy, especially in the countries of the former Soviet Union. In the behind-the-scenes, sausage-making policy process, it gained a near veto power. DRL was not overly pleased with Kazakhstan because it had not quickly become a free-market democracy after independence. Political opposition parties, when they were even allowed to exist, were tightly controlled, and civil-society non-governmental organizations (NGOs), that the United States and the European Union supported, were matched by government-created and, some said, subservient NGOs, sometimes derided by DRL with the ironic acronym, GONGOs – government-organized non-government organizations. Further, the working level in DRL bemoaned what they called President Nazarbayev’s “cult of personality,” because he was allowing things, like the new, international university in Astana, to be named for him – “and he isn’t even dead yet!”

To make matters worse, any high-level OSCE meeting, whether an exalted summit or “just” a ministerial, includes official side meetings by the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) for the host-country’s NGOs and their international supporters. But President Nazarbayev decided that such meetings would not be part of his summit – only his GONGOs would be allowed to participate. After much contentious behind-the-scenes and often late-night negotiation, the compromise was reached that ODIHR could indeed have its traditional NGO meetings but not at the official summit site in Astana’s New City. Instead, they would take place several miles away at a university in the Old City. No one was really pleased, but the day was saved with compromise on both sides.

My job was to keep Foreign Minister Kanat Saudabayev, whom I knew well from his time as Kazakhstan’s Ambassador to Washington, up to date on the level of the U.S. participation in “Nazaybayev’s Summit.” I knew beyond any doubt that President Obama would not be travelling to Astana. But as for the name of the real U.S. government participant, I had to continue using the standard phrase, “It’s still under discussion.” Saudabayev was not overly pleased. As the date of the summit approached, Saudabayev became increasingly exercised, insisting that he had to tell “the boss” who was coming from Washington. With my fingers crossed behind my back, I continually responded, “It’s still under discussion because of complicated schedules, but I assure you we will have very high-level representation.”

President Nazarbayev and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton Meet at the OSCE Summit, December 2010

In fact, DRL lost their hard-fought battle to get the U.S. government to boycott the OSCE summit in Astana. But it wasn’t until her plane was actually in the air that I was finally informed that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton would represent the United States. President Nazarbayev was satisfied. Foreign Minister Saudabayev was satisfied because President Nazabayev was satisfied. And all went well. As often happens in the world of diplomacy, what you see in public is the ready-for-the-cameras final result that hides the hair-pulling and sleepless nights of high drama behind the scenes.